- DOWNBEAT, December 2023

WOODSHED

MASTERCLASS by ALEX WEISS

How the Church of John Coltrane Led To My Discovery of Music Therapy

Diane is a 57-year-old woman with Down syndrome. Our time together once a week at Bergen Beach is usually spent singing gospel songs together. The familiar music from her church-going days still linger in her memory. We’re able to share time together by visiting these songs she has sung her whole life. But she does not speak any more. When I begin with her by strumming through the chords of “Amazing Grace” in a slow and rubato way, it serves as a cue for her, and her ability to vocalize through the song comes to life. Diane has been unable to speak for a few years now. But she can still sing.

My journey into music therapy started with John Coltrane. Or more specifically, the John Coltrane Church of San Francisco, founded by Archbishop Franzo King and his wife, Mother Marina King, who were so moved by Coltrane’s 1965 album, A Love Supreme, that they formed an entire church around it and sought to canonize him. The two years that I spent with this church from 1994 to 1996, were pivotal years that seared into me that music can be a form of ministry and service to others, not just entertainment or art.

I was in my early twenties, a saxophonist living in San Francisco. Two hundred thirty miles south of me, down in San Luis Obispo, my father was battling terminal cancer. Though he insisted on not disrupting my and my sister’s lives as much as possible, I went back and forth as often as I could. A friend of mine told me about the church. “A place that celebrates Coltrane as he’s the patron saint of the church, and the services are amazing as they’re filled with his music.” After my first Sunday service, I was hooked. I wanted to go every week. And I did.

Supposedly referencing his years of recovery from heroin addiction, in the liner notes to A Love Supreme Coltrane wrote, “I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening... At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music.” These words became the foundational backbone of the church, which used the album itself as religious musical text to form their worship. Although I had been raised to look askance at organized religion, this type of worship—through music—felt different.

Back in San Luis Obispo, the chemo and radiation had taken a toll on my father’s body, and the smallest activities were hard for him to do. I helped his wife prepare his food and supported him as he shuffled to the table. Sometimes we took slow walks up the road, as best as his wasted body could manage. Other times, we just sat in the backyard, and let the sun drift off our faces.

After one visit, I couldn’t shake the memory of my father’s frail body. The next day when I went to church, I was asked to come up and lead the congregation in “Acknowledgement,” the first movement of A Love Supreme. Some of the most accomplished musicians in the city stepped aside to let me lead that first movement. As I played the signature arpeggio phrase, feeling surrounded by people who showed their caring through the music, I felt the darkness inside me lift.

The original church building on Divisadero Street was a modest storefront of a place. But inside, it was outfitted with a beautiful altar, pews, and iconography made by a painter named Mark Doox. He had painted masterful portraits of both Coltrane and Jesus (who was portrayed as black and wearing dreadlocks) in the style of Russian orthodox icons. A drum set, piano and upright bass sat patiently in the front by the altar. Despite its modest exterior, the place felt like a sanctuary.

Sunday service began with fervent preaching from Archbishop King, whose sermons weren’t liturgical, but spoke piercingly of political injustice and social issues. Then the service would seamlessly transition into the music of A Love Supreme, and passing through all its four movements were the antiphonal prayers formed by Archbishop King’s words.

There were three saxophonists in the church’s core sextet: Archbishop King, his son Franzo Jr., and the Bishop Roberto De Haven. The pianist was Fred Harris; the bassist, Juanika King; and the drummer, Archbishop King’s other son, John. The Sisters of Compassion choir sang lyrical accompaniments while they played A Love Supreme. Together, the music they made was powerful. And when the sextet played, they sounded like the greatest Coltrane band in the world. The spirituality of A Love Supreme is the most important element of Coltrane’s album, but one that is often lost in interpretation. But the sextet played it with the full gravity, devotion and beauty that it deserved.

The great Roberto De Haven, a known jazz player and saxophonist in and around the Bay Area, was also my mentor. He had a gentle demeanor and spoke in a rich, low baritone. Once a week, down in the church basement, Bishop De Haven and I would read through the Charlie Parker Omnibook, and then improvise freely with two saxophones. Sometimes, Roberto would play the drums. We’d listen to all kinds of music—from Parker to Hodges to Ornette Coleman to Coltrane, and much more.

We’d only stop when we truly felt the time was over. He told me to pay him what I could, and he would give ten percent to the church. I remember his complete and genuine dedication. The music was a specific kind of gift and like nothing I had ever received before. He showed me how important and affirming music can be for myself. How the discipline of music, listening to it, and cultivating it with assiduity and commitment is a worthy practice in itself. Years later when I became a father, I gave my son the middle name Roberto.

The church also ran a soup kitchen after service, twice a week, Wednesdays and Sundays. All kinds of people came—people who had attended service, homeless people, and people who lived in the neighborhood. For two years, working in that soup kitchen on those two days felt like learning how to make the spirit of Coltrane’s music concrete, learning the practice of being of service to others.

In 1998 my father passed, and some years later, I eventually moved to New York City, where I was a gigging musician with a day job. Then, when that job started looking uncertain, I discovered music therapy. Alan, a pianist friend of mine, was working as a music therapist after completing a graduate degree. We met up and talked about his experiences during the program and his work as a therapist. What struck me was the remarkable range of those that could be helped, from neonatal babies to the geriatric population, to soldiers with PTSD.

I worked with a man whom we’ll call “Jack” for about six months in 2010. We would meet in a music room of sorts the music therapy department had in one of the buildings owned by Beth Israel hospital in Manhattan. It was outfitted with all kinds of percussion, mallet instruments and Jac’s instrument, a piano. Jack had been in and out of Section 8 housing and homeless shelters for years. So, these once-a-week meetings served a bit as a refuge for him. It was a place for him to travel to, and go with the knowledge that he’d have access to a piano and be able to play his music.

Jack was an Afro-Cuban piano player for many years, and his dexterity and overall ability on the instrument was wonderful. To these sessions I’d bring my tenor saxophone. We would run through all kinds of standards like “Mambo Inn,” “Caravan,” “Manteca” and “Perdido.” These sessions gave Jack the opportunity to relive his musical days and remember the good times he had when he was young in an environment that was safe and if needed, a place where he could be vulnerable to feel nostalgic.

Occasionally, he would abruptly stop playing in the middle of a song, pause for a bit and then turn around to me to recall a specific movement in time that had to do with making music, and sometimes to recall a time with a loved one. I would put my horn down and listen to his story. Then I’d ask him questions to further explore the memory, if it felt like the right thing to do. My goal was to get him to reflect on the positive aspects of the memory, to spotlight the joyous times within his story. And sometimes the story was one of loss. His wife passed away years ago, and letting him tell the story of her passing with an empathic ear was all that he needed.

When I started working as a music therapist, it highlighted for me one of the most beautiful things about music: the myriad different ways it can be made. Sometimes, just two simple chords played on a guitar, toggled back and forth slowly, can be precisely the music needed to help.

When I interned as a music therapist at the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit of Beth Israel, my job was to use a guitar to calm distressed infants, as it was critical for them to conserve energy. An alternating arpeggiation of two chords (e.g. C and F) played very slowly, quietly, and close to the incubator glass, would almost always calm down the baby. The monitors showed the distressed spike in the baby's vital signs drop. My being able to calm the baby down this way meant a further intervention by a nurse or a doctor was not needed. And watching those impossibly tiny wrinkled hands and feet stop their flailing, just because I played those chords, filled me with wonder. They instinctively responded to music even before they’d had the chance to be properly in the world. The music calmed them down because on some level, they could sense the presence of another, just as their mothers’ heartbeats had been their constant, reassuring companion through their whole gestations.

In music therapy, what’s important is not the skill or artistry of the music, but that it gives us a way to be in communion with each other. And healing resides in that human connection. That was the spirit of what Coltrane wrote in those liner notes to A Love Supreme, the album that inspired the formation of the church that started me on this journey. Coltrane thought music was a profoundly shared experience and that it could be a gift that we could give each other. And each time I listen to Coltrane’s version of “I Wish I Knew,” or see a baby calm its restless roiling because two chords are played, I feel that too. The beauty of the sharedness of music, and how it can help heal.

- Jazz Trail

Alex Weiss - Most Don’t Have Enough by FILIPE FREITAS

The sociopolitically-themed Most Don’t Have Enough, a stark set of incandescent hybrid pieces by Brooklyn-based saxophonist and composer Alex Weiss, is inspired by the world of our times: the damage caused by Trump’s presidency as well as the violence and precariousness seen a bit everywhere around the world. He leads an amazing quintet that includes luminous stars like the soprano saxophonist Dan Blake and drummer Ches Smith.

All but two of these nine tracks are originals. The attractive themes, the easy flow with auspicious time shifts, and the quality of the arrangements are immediately found on “The Leonard Nimoy Method”, where an indie rock melodicism mixes with avant-jazz angularity to please the ear. The song, dedicated to the actor of The Invasion of Body Snatchers, is stirred up by a tenor solo delivered with passionate lyricism and deep intensity, a fine collective envelope, and wonderful soprano rambles.

Blake also channels his positive vibe and energy into the final moments of “Homage to Elijah Cummings”, the first of two pieces guesting the virtuosic Spanish pianist Marta Sanchez. The other cut she participates in - delivering an unorthodox statement - is the closing “Akira: Sun and Moon”, whose odd-meter groove altered periodically with a 4/4 rock drive are meant to celebrate Weiss’s son, Akira.

Disgusted with what Trump brought to America, Weiss makes “Your Dark Shadow Arrives at the Door” unfold with 3/4 curiosity, whereas in “Organized Religion”, which mentions another known predicament, there’s a combination of rock muscularity (reinforced with Yana Davydova’s distorted guitar) and jazz fluidity (in the form of unreserved unisons, counterpoint and polyphony).

The two gorgeous covers presented here are swinging attractions with audacious melodic lines, well-shaped figures, and deft runs conducted with purpose. We’re talking about Chris Speed’s “Really OK”, which brings to our mind the music of Herbie Nichols and Steve Lacy; and “Humpty Dumpy” by the groundbreaking saxist Ornette Coleman, another tremendous influence on Weiss’s musical vocation.

The rhythms and concepts might not be a novelty but Weiss’s tunes bounce with zesty enthusiasm. It’s a feel-good record that runs a nice gamut between substantial rock and accessible avant-jazz.

https://jazztrail.net/.../alex-weiss-most-dont-have...

PS 133 William A. Butler School

THUMBELINA

- The New York City Jazz Record

NEW YORK's ONLY HOMEGROWN JAZZ GAZETTE

by Marco Cangiano

- All About Jazz, Terri Hinte

Alex Weiss’s idiosyncratic vision of post-bop jazz finds a new apex with the tenor saxophonist-composer’s February 24 release of Most Don’t Have Enough (ears&eyes). Weiss’s third album as a leader is also his first with Glad Irys,hisworking quintet since 2019 comprising soprano saxophonist Dan Blake, guitarist Yana Davydova, bassist Dmitry Ishenko, and drummer Ches Smith, with pianist Marta Sanchez adding her distinctive stamp to two of the album’s nine moody, mysterious tracks….

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/news/saxophonist-composer-alex-weiss-..

- Saxophonist/Composer Alex Weiss Exhibits His Surrealist Jazz Conception on "Most Don't Have Enough," Due Feb. 24 from Ears&Eyes Records

https://www.prweb.com/releases/saxophonist_composer_alex_weiss...

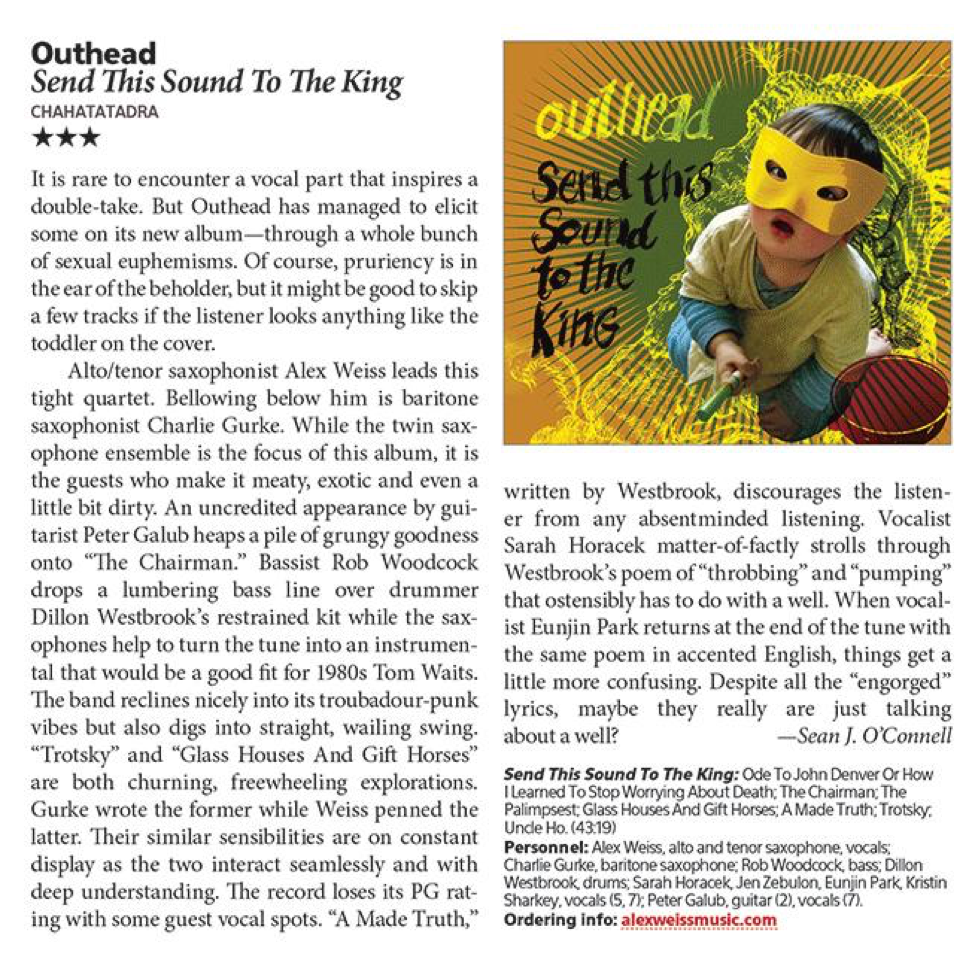

- DownBeat, Sean J. O’Connell

http://www.downbeat.com/digitaledition/2015/DB1502/single_page_view/77.html

- All About Jazz, Glenn Astarita

Outhead: Send This Sound To The King

This San Francisco Bay-area unit propels a renegade New York downtown-ish vibe amid notions of punk jazz and the occasional flight towards the free zone. They also rock hard as guest guitarist Pete Galub inserts a serrated edge with his avant, jazz fusion vernacular. Nonetheless, they're young artists with big ideas. Besides the instrumentalists notable chops, it's the memorable compositions that segregate the band from many of its peers. Featuring guest vocalists who help proliferate a melodic Indie rock groove on the final track "Uncle Ho," the production contains a heterogeneous mix, fundamentally centered on a progressive jazz-centered stream of consciousness.

Indeed, the musicians generate good cheer via these largely up-tempo works; although, on "The Chairman," Galub imparts some steely toned angst with his howling, electrified licks in parallel with saxophonists, Alex Weiss and Charlie Gurke's undulating impetus over a medium-tempo cadence. Each piece poses distinct stylistic components as the band projects an entrepreneurial mindset, witnessed on the asynchronous pulse that encapsulates "Glass Houses & Gift Horses," where the saxophonists blustery and soulful unison phrasings segue to a blitzing 4/4 groove and fractured lines. Ultimately, they stitch a complex but attainable storyline together, leading to a rather ominous downward spiral.

Diversity is a key driver, evidenced by the spoken word piece "A Made Truth," shaped by bassist Rob Woodcock's prominent ostinato motif and Galub's spooky lines, intermixed with a drifting melody. And from an improvisational perspective, the saxophonists don't rely on one primary mode of attack, as they integrate impassioned treks into the red zone during choice movements. Simply put, this album marks one of those unforeseen surprises that arrived in the mail. Hopefully, the musicians will pool their creative resources for subsequent endeavors of this ilk or to extend matters into other regions of sound and scope.

Track Listing: Ode to John Denver or How I Learned to Stop Worrying about Death; The Chairman; The Palimpsest; Glass Houses & Gift Horses; A Made Truth; Trotsky; Uncle Ho.

Personnel: Alex Weiss: alto and tenor saxophone, vocals; Charlie Gurke: baritone saxophone; Rob Woodcock: bass; Dillon Westbrook: drums; Sarah Horacek: vocals (7); Jen Zebulon: vocals (7); Eunjin Park: vocals (7); Kristin Sharkey: vocals (7); spoken word (5); Pete Galub: vocals (7), guitar.

https://www.allaboutjazz.com/send-this-sound-to-the-king-outhead-self-produced-review-by-glenn-astarita.php

- Art & Culture Maven, Anya Wassenberg

Outhead to Release ‘Send This Sound to the King’

Outhead - the quartet of alto/tenor saxophonist Alex Weiss and baritone saxophonist Charlie Gurke with double-bassist Rob Woodcock and drummer Dillon Westbrook - pursues a low-slung, roughhewn aesthetic that's equal parts free-jazz and art-punk, brimming over with vim and vigor. Outhead's second album - Send

This Sound to the King, to be released October 14, 2014 via Chahatatadra Music - juxtaposes catchy melody and swinging grooves, headlong caterwaul and dreamy spoken word. Guest guitarist Peter Galub provides spiky six-string atmosphere to several tracks, and multiple voices are heard, male and female.Send This Sound to the King is the sound of both edge and allure.

Outhead's new album is the follow-up to the band's 2008 release, Quiet Sounds for Comfortable People, which was a favorite of Downtown Music Gallery's Bruce Gallanter for its "inventive dynamics" and "fabulous groove." He heard a kinship with Ornette Coleman's two-sax band with Dewey Redman, while Weiss lists Archie Shepp and Roland Kirk as further references, for both their stentorian roar and the theatricality of their '60s work. The sly humor and sheer accessibility of Send This Sound to the King makes Outhead akin to John Lurie's iconic downtown New York band the Lounge Lizards, while rock fans may even hear echoes of the baritone-driven, post-Beat stylings of vintage indie-rock trio Morphine at times. Yet for all its hip influences and antecedents, Outhead is above all an individualist outfit, playing music that isn't quite like anything else out there.

Outhead's second album kicks off beautifully with the majestic, melody-rich"Ode to John Denver, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying About Death," a woozy rubato spiritual by Weiss in a classic Albert Ayler mode, with a droning foundation of harmonium and arco bass for an East-meets-West feel. Next comes "The Chairman," a laconically catchy tune by Gurke that's blessed by Woodcock's grooving, textured bass playing and guest electric guitar by Peter Galub, who lends a rock'n'roll feel to the track - particularly with his fantastically wild, wailing solo near the end. Weiss' "The Palimpsest" makes a nod to John Zorn's Masada songbook; the composer's alto leads with the faintly Middle Eastern melody and a cry in his tone, though Gurke's baritone soon entwines serpentine around it for their characteristic sax blend.

"Glass Houses and Gift Horses" is a headlong rocker by Weiss, with a deceptively sophisticated form. The composer plays tenor, while Gurke's solo takes advantage of multiphonic effects and the overtones possible on the baritone. Westbrook, who has a Masters in Fine Arts degree in poetry, wrote the music and verses for the artfully produced soundscape "A Made Truth," with the sexual subtext of the words made plain in the initial sly recitation by Sarah Horashek and then undercut oddly and humorously by Eunjin Park's less-native way with the same lyrics."Trotsky" is a groovy free-bop number by Charlie in the early Ornette Coleman manner, the harmolodic icon being a prime influence on every member of the band. The album's offbeat closer,"Uncle Ho," features music by Charlie and words by Alex, with a chorus of women's voices taking a key role. Roland Kirk'sVolunteered Slavery is a key influence here, though with more demented humor in the words than political fire. The sound of Alex and Charlie's twinned saxophones is a textural highlight, as on the entire album.

https://www.artandculturemaven.com/2014/09/arthouse-jazz-outhead-to-release-send.html

- Gapplegate Music Review, Greg Edwards

Outhead, Take This Sound to the King

Life may not be like a box of chocolates lately, to refer to Mr. Gump, because we seem to know what we are getting, for good or ill. But it still applies to music. I get CDs in the mail often enough where I have no idea what it's going to be. Outhead's album Take This Sound to the King (Chahatatadra Music) serves as a good example. What was it? Putting it on I found it was something very good. Very modern jazz with a compositional base and a definite outside edge.

The credits list Alex Weiss on alto and tenor, Charlie Gurke on baritone, Rob Woodcock on acoustic bass and Dilton Westbrook on drums. Weiss and Gurke provide most of the compositions, with one by Westbrook. There is a skronky electric guitarist on a cut or two who sounds good, but he (or she) is not listed.

The music is very forward, rockish at times, contemporary like Morphine just a hair, but no, not entirely. The two-horn parts are intricate and weave well with rhythm-section routines. The band has a good thing going with Weiss and his hip solo style, both fleet and smart, with a full tone that doesn't sound like others so much. Gurke has a good sound and presence on baritone, too.

And the ensemble as a unit has real clout. It's new and hip sounding, with pulse and dash, and a certain "this is our music" and like it or not directness that appeals.

It's quite good. Different enough that you don't feel like you are repeating yourself when you put it on. Better than a box of chocolates! No doubt.

http://gapplegatemusicreview.blogspot.com/2015/01/outhead-take-this-sound-to-king.html

- Improvijazznation, Dick Metcalf

I have a feeling most of the kings of yore wouldn’t quite be able to “grok” what Alex & his bandmates (fellow saxophonist Charlie Gurke, bassist Rob Woodcock, drummer Dillon Westbrook and special guests on guitar and vocals) are doing here. I was strongly attracted to the spoken-word they have going on with tunes like “A Made Truth“, but the jazz (in the tradition of players like Ornette, Rhassan Roland Kirk & players of that stature) is paramount in what they’ve put together for your aural excitement! The opener, “Ode to John Denver or How I Learned to Stop Worrying About Death“, will totally blow you away… holding you spellbound in the process (nothing like you imagined when you saw that title (lots of tension/release to keep you wondering, too). It was the 8:01 “The Chairman” that got my vote as personal favorite of the seven pieces offered up… I give Alex & his fantastic crew a MOST HIGHLY RECOMMENDED for jazz lovers who want something different; the “EQ” (energy quotient) rating is 4.99. You can get more information at Alex Weiss’s website.

- Jazz Weekly, George Harris Alex Weiss plays alto and tenor sax on this mix sounds with Charlie Gurke/bs, Rob Woodcock/b and Dillon Westbrook/dr. The sounds come across as a mix of vintage Charles Mingus, but without the neurosis and Ornette Coleman yet without the iconoclasm. Edgy sounds meld together with Woodcocks’ bass leading the way on “”A Made Truth” and the horns lock and pull together before splitting apart on “Trotsky.” Dark tones and moods trudge along on the lonely “The Palimpsest” as Weiss’ alto makes some poignant points. Voices are brought into a few equations, with a spoken word poem by Kristin Sharke on and Weiss and Pete Galub joining in “A Made Truth.” More vocals on “Uncle Ho” and a Monkish-inspired “Glass Houses & Gift Horses” make the disc feel like a mix of influences and ideas that mostly stick to the kitchen wall.

- Midwest Record Recap, Chris Spector CHAHATATADRA - Mos Eisley Music Blog, Jonas Kolbe Being influenced by various genres like punk rock, Alex Weiss, alto saxophonist and member of the group Outhead, might not be your typical jazz saxophone player. On "Send this Sound to the King" he rejoins with his fellow musicians Charlie Gurke (baritone saxophone), Rob Woodcock (Bass) and Dillon Westbrook (Drums) to play an highly interesting brand of jazz. - Shepherd Express, Dave Luhrssen On their second album, the bi-coastal quartet Outhead takes the trail opened by the ’60s jazz avant-garde, but with a determination to hit audiences in the gut rather than sail over their heads. Rock elements echoing the sax-driven Morphine can be heard, along with enough melody in their saxophone cacophony to suggest Henry Threadgill at his most accessible. Alex Weiss and Charlie Gurke lead with their saxophones over the pulse-beat grooves and rolling thunder percussion of bassist Rob Woodcock and drummer Dillon Westbrook. Guest guitarist Peter Galub adds electricity on a few tracks. - Nextbop.com, Anthony Dean-Harris http://nextbop.com/blog/outheadsendthissoundtotheking - VinylMine, Phontas Troussas http://diskoryxeion.blogspot.gr/2014/11/outhead.html - Monsieur Delire, Francois Couture http://blog.monsieurdelire.com/2014/10/2014-10-28-outhead-ken-thomson-and.html - Wondering Sound, Dave Sumner http://www.wonderingsound.com/new-jazz-week-eple-trio-luca-ciarla-quartet-

throttle-elevator-music/

- Jazz Inside, Eric Nemeyer Feature interview in November 2014 issue - Musica Jazz Magazine (Italy), Alessandra Andretta Best New Jazz in Dec 2014 issue. - Tchaicai's Five/ Six Points Plays George Wein's Jazz Festival, 2010 John Tchicai's Five Points is a quintet with guitarist Garrison Fewell, fellow reed player Alex Weiss, bassist Dmitry Ishenko and drummer Ches Smith. - Outhead / Quiet sounds for Comfortable Music, 2008

http://rotcodzzaj.com/42-2/improvijazzation-nation-issue-152/issue-152-reviews/

http://www.jazzweekly.com/2015/01/outhead-send-this-sound-to-the-king/

OUTHEAD/Send This Sound to the King: Oh, how can you not respect a bunch that tells you right up front they're a pomo art house bunch? Commemorating the no wave vibe with it's roots in free jazz, this the sound of hipper malcontents into jazz everywhere this season.

http://midwestrecord.com/MWR873.html

Though I can't seem to recognize any specific punk rock elements on this album besides a noisy guitar here and there, it still carries an individual style and spirit. A track like "The Palimpsest" might be a good example: The first thing we can hear is the perfect blend of two saxophones playing together. The next thing is the rhythm section kicking in, which is more or less the trademark of this group. Steady rhyhtms and a dynamic bass provide a solid groundwork in each track for the melodic saxophone symbiosis. "The Chairman" is probably the most grooving song on "Bring this Sound to the King". It also shows that this group knows how to arrange and orchestrate - There is a clear structure to each tune and every solo and improvisation that you will hear is perfectly embedded in it. Playing smooth notes while bringing that certain element of surprise at the same time is what makes this band unique.

http://mos-eisley-music.blogspot.de/2014/09/outhead-send-this-sound-to-king.html

http://expressmilwaukee.com/article-permalink-24376.html

Surprisingly One Long Minute was recorded after only two live performances but the band sounds seasoned, without an ounce of tentativeness.

Each member except Ishenko contributes compositions and the band really seems inspired by each other's efforts. Tchicai gets off a fiery solo on Smith's "Anxiety Disorder" and his bass clarinet (uncredited) roams deeply on Fewell's "Venus." Weiss' arrangement of the theme to Akira Kurosawa's "Yojimbo" is just a brief theme statement but fits perfectly into the program. Tchicai's "Parole Ambulante" is a typical languid theme delivered over a free rhythm with beautiful voicings given sonic depth by Ishenko's arco bass work. One wonders what this band will sound like by the time of the next disc.

By ROBERT IANNAPOLLO -All About Jazz

http://garrisonfewell.wordpress.com/2010/07/01/tchicais-

fivesix-points-plays-george-weins-jazz-festival/